How to Write User Stories That Matter

UI/UX Design

User Research

From the moment we are born, we love a good story. Even those who don’t enjoy reading still love some form of storytelling. Whether listening to gossip around the office or reading news, stories are a vehicle for understanding the world - a way to relate information in a fashion that lets people empathise.

And that’s why user stories are so successful in business settings. Understanding a user/customer is all about knowing their problems, needs and personalities. What better way to do that than to build stories that help businesses and all those involved with the customer better understand their users?

Defining need with user stories

User need is a core concept in Agile methodology and something we talk about a LOT here at KOMODO. You can’t build a business without understanding users' needs. That’s why so many startups fail, so many new apps crash and burn and even why some established successful businesses have to scrap new projects (we’re looking at you, Google Glass.)

Understanding a user’s needs helps prevent failed projects by ensuring that your potential audience actually requires something you’re going to offer. User stories are a UX-based exercise that incorporates user needs into a clear ‘story’.

How to write user stories

In traditional UX, user stories follow a defined structure. This structure is focused on user goals. You should aim to write them so that they are accessible and can be collaborated on by stakeholders, team members and the UX team. Typically, you write user stories towards the beginning of a project to help define goals and actions.

If you’re looking online for how to write user stories, you’ll probably find this Agile structure:

“As a… I want… so that”

As a: the person doing the action/goal - who are they, what is their role?

I want: what action do they want to accomplish/achieve? (This is often where a user need is most referenced, usually incorrectly - but we’ll break this down more in a moment.)

So that: what added value do they get as a result of the action?

For example, a user story may read: “As a tenant, I want to book repairs online so that I don’t have to call my landlord.”

User stories help to keep a tight focus on user needs. They can be the beginnings of your features and functionality. However, even though we are an Agile-focused product studio and user stories are traditionally created in this way, we’d say they are far too narrow to truly understand a user.

Why? They lack empathy and context. A user story in this format misses many of the driving factors behind what a user actually wants. They are written to try and define UX outputs - but they miss the research needed to really know what a user is trying to accomplish.

If we create a random example such as:

“As a potential customer, I want to research local cafes so that I can decide which to visit.”

But this story lacks context. The customer ‘need’ is often misunderstood - and rarely given enough thought. What if the user’s ‘I want’ is instead that they want to see pictures of cafes rather than reviews or listings. User stories lack context because they need something else. You must know who your customers are and what their goals look like before writing clear user stories.

To do that, you have to think more widely about user personas and journeys.

User stories from personas

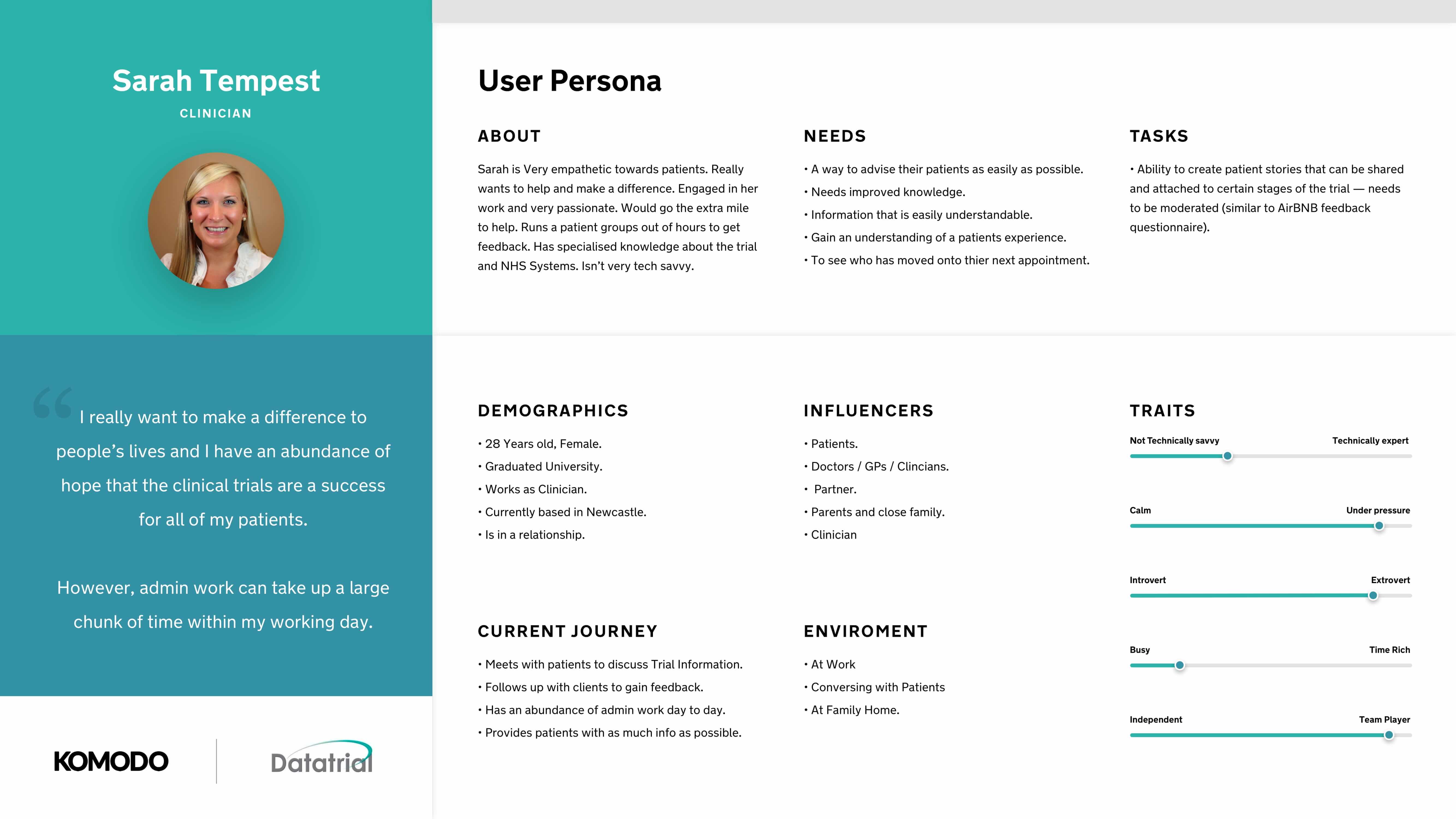

You should aim to create user personas before you ever think about writing out a user story. A persona maps out your users’ background, identifying their thinking processes, demographics, lifestyle, etc. From this, you’ll define user needs - rather than trying to create stories without understanding context.

For example, a healthcare company approached us to create technology to help patients undergo clinical trials; we knew empathy was key. We had to understand the users’ needs, taking into account their conditions and circumstances. The solution had to reflect their abilities and emotions rather than solely focusing on what they wanted.

To do this, we built detailed user personas. By collaborating with the client and with patients using user research, we described common user types. We built them into categories which included:

Needs - what the user needs from your solution - but also what they don’t need (they need, for example, to spend as little time as possible using an app so they can focus on their family)

Tasks - what the user type is actually doing to necessitate an app (booking appointments, accessing contacts etc.)

Demographics - broadly broken down by age, location, career etc

Influencers - who impact their decision-making process. Friends, family etc.

Current journey - the situation the user is currently in before you’ve built a solution. Here, you should be able to see a clear justification of your idea - if their current journey clearly lacks what your app/product will provide, there’s likely a market need.

Environment - where will they use the app/product?

Other factors such as technical competency, for example, can be built into this persona but what’s most important is the idea of empathy and understanding. It’s easy to fall into the habit of generalising when putting together personas and forgetting that people have genuine needs and complicated decision-making processes. In this example, the influencers were important as they will impact how a patient interacts with technology (if they can use your app to cut down on complexities and have more time with their family, that’s a big win).

User story mapping

Unlike the ‘As a… I want… so that’ structure of user stories, a user story map traces your user personas through the entire journey of your project. In the example above, we mapped out the key stages of this healthcare client’s journey: enrollment, screening, first visit, post-visit, trial end.

We then listed actions and thoughts by the user for each of these stages, defining their needs based on where they were in the journey and their goals for each part of it. Rather than summarising everything into single stories, we instead created a full map of what users were doing at each stage.

Only then would we begin to see possible ways our technology solution could help. We now had defined needs at each stage of the journey, understanding the patient’s backgrounds and motivations. Now we could use empathy to map proposed needs and challenges to solutions.

This was done for each user type, such as the clinicians, giving us a broad picture of which challenges each user type faced.

It is from this background that good user stories are created. We can take the challenges presented in the user journey and begin to ideate on features/functionality that can be turned into multiple user stories based on real, tangible requirements.

“As a patient, I want to reschedule an appointment so that I can attend my wife’s birthday party.” - in that example, we’ve created a clear technology requirement - the ability to reschedule appointments - and also understood the emotive context behind it. We now know that the process should be simple and as convenient as possible so that the user won’t worry about it.

We also know that from a clinician’s journey, rescheduling can cause issues, so we’ll factor that in with their own user story, such as “As a clinician, I want to know when rescheduling occurs, so that I can manage my time and ensure the patient does not miss critical treatment windows.”

Empathy > Technical Requirments

Phew. That’s a long way of discussing the importance of user stories driven by empathy rather than technical requirements. When you work on a digital product, you must understand who your users are and what their lives are like before mapping out their needs.

Only through empathy and context-driven thinking can you build user stories beyond technical requirements to add value to your users’ lives.

Got an idea? Let us know.

Discover how Komodo Digital can turn your concept into reality. Contact us today to explore the possibilities and unleash the potential of your idea.

Sign up to our newsletter

Be the first to hear about our events, industry insights and what’s going on at Komodo. We promise we’ll respect your inbox and only send you stuff we’d actually read ourselves.